|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

Is SpaceX losing it?

That question has two parts. We'll talk about Starship first.

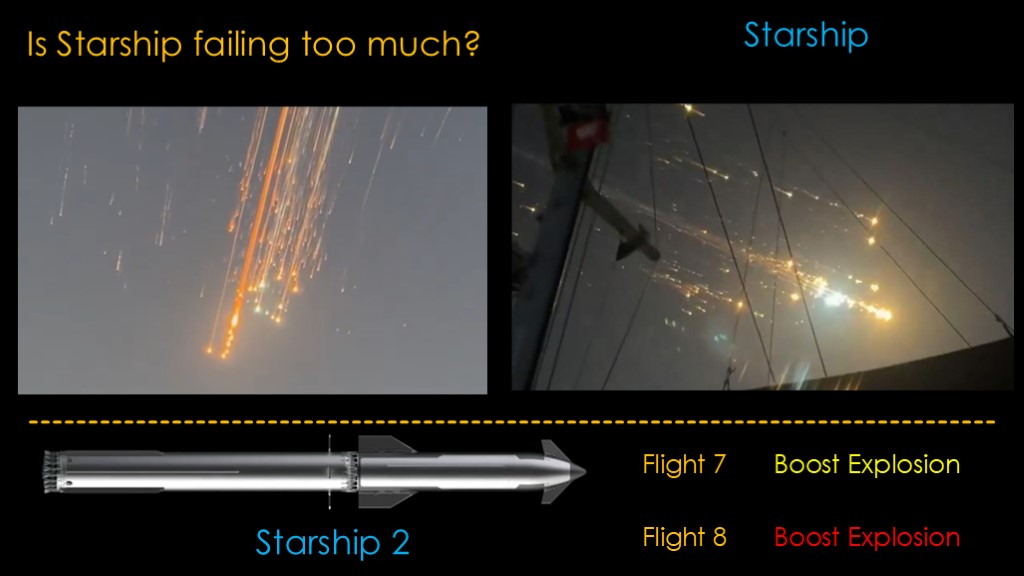

You probably know that starship flight 7 and flight 8 both exploded on ascent. That seems bad, but is it a meaningful sign of a bitter problem?

We need to look at the bigger picture to answer that question.

I've done two videos on the starship development approach and why it's different, and you might want to go watch this one

And this one at some point.

With that in mind, we can take a look at the starship flight history.

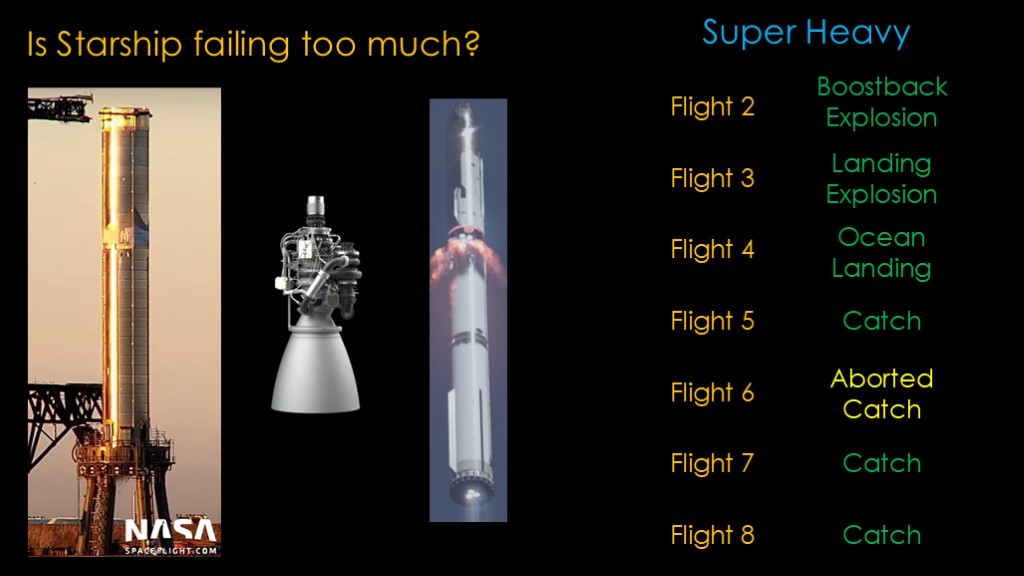

And we'll start with Super Heavy. Conceptually, Super Heavy is a big Falcon 9, and SpaceX understands Falcon 9 very well.

The new parts are dealing with a new rocket engine. Raptor is both brand new and uses autogenous pressurization - the propellant tanks are pressurized using gas from the engine preburners. This is a new technology for SpaceX and not something that you can test without the rocket engine integrated in the stage.

Super Heavy is also designed to stage quickly - Falcon 9 takes a long time to flip end for end before relighting its engines, while super heavy does hot staging and flips under power. That's also something new.

It's therefore not surprising that there were issues in flight 2 and 3, but since then super heavy has performed great - two ocean landings and successful catches on three out of three attempts. It quickly progressed through the issues and made progress on every flight.

This was about the level of progress I expected, and we should expect to see reused boosters flying fairly soon. Great progress.

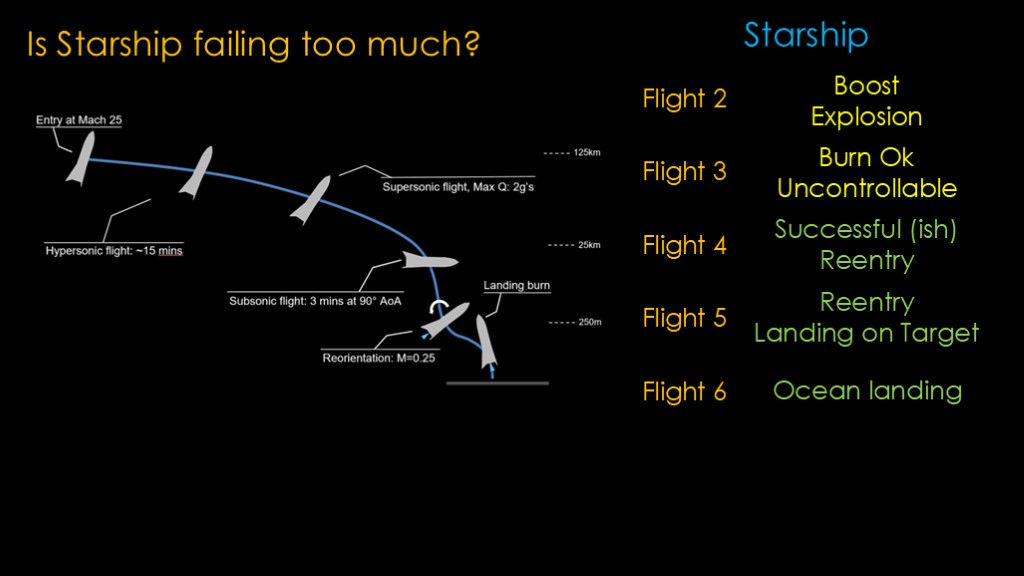

Starship has always been the challenging part. It not only has the new engines, it has a brand new reentry approach and is controlled during reentry with fins. I've always considered starship reentry to be the most challenging part of the entire program .

The first two flights had an explosion on boost and then a successful boost followed by a loss of control that precluded the reentry test. That was unexpected. Raptor is a new engine and there are likely more issues there, but the loss of control in flight 3 is concerning.

Based on the first two flights, I would say that starship is in trouble. If it was a conventional program. Since it's not - and we now that SpaceX is heavily devoted to incremental design - then it's not a big problem.

If we look at flights 4-6, that would seem to be true. Flight 4 makes it to the target trajectory and miraculously makes it through reentry and flights 5 and 6 repeat that with better results. Steady progression and moving towards orbital flights, starlink payloads, and catching starship back at the launch site.

Which brings us to the recent flights 7 and 8 which produced impressive fireworks when starship disintegrated during the boost portion of the flight.

This is the introduction of the block 2 version of starship. It reportedly (listen to broadcast) has thousands of changes from block 1, including redesigned fins to protect them better during reentry and 25% more propellant.

How should we react to this double failure?

The pessimistic perspective is that starship took a big step backwards with two failures in a row, and the optimistic perspective is that starship 2 is a new vehicle and that we should expect incidents in this situation.

So I'm going to stick with my usual answer, which is "I don't know", or - to be a bit deeper - I don't think anybody outside of SpaceX has enough information to know whether to be alarmed or not.

I do have a couple of observations.

The general feeling amongst those who think a double failure like this is unacceptable seems to be that SpaceX should be more careful and that their "cowboy" approach is catching up with them.

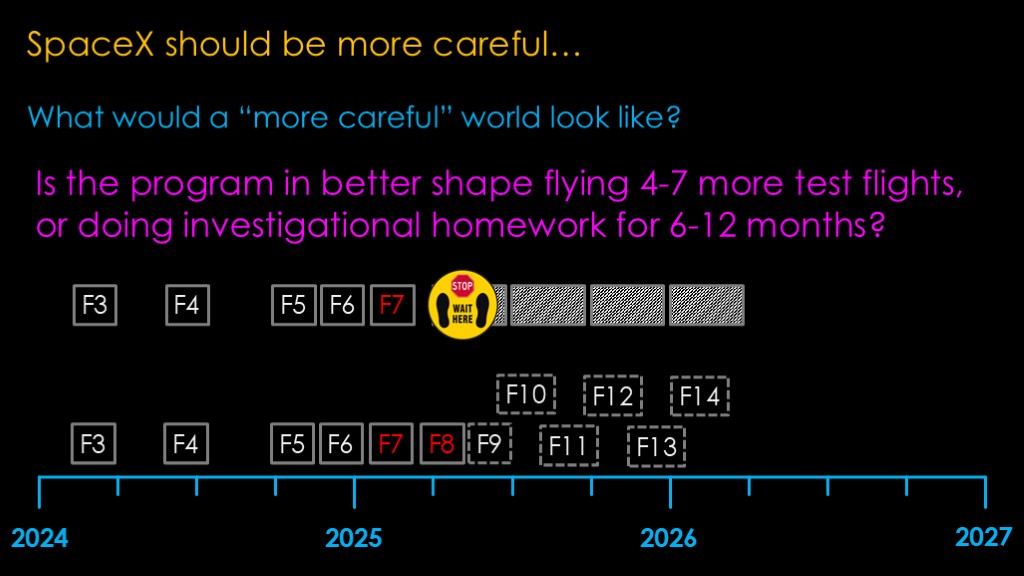

Interesting idea. Let's look at the recent flight timeline...

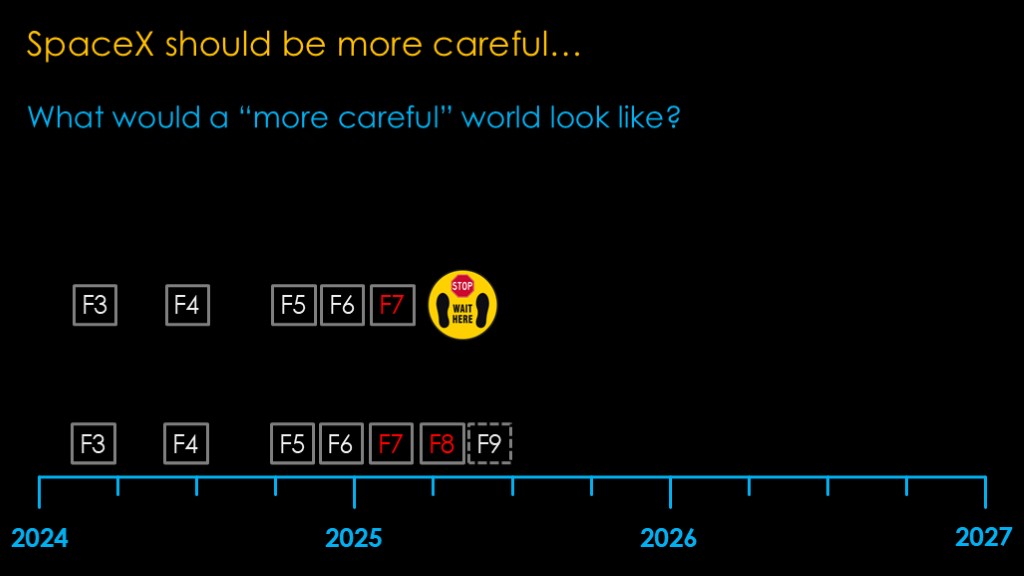

In 2024, Starship launched 4 times, in March, June, October, and November. In 2025, we had flight 7 in January, Flight 8 in March, and flight 9 coming up in April/May...

What would a more careful world look like?

It would at least involve a significant stop to figure out the details of what caused the explosion on flight 7 and corrective measures to make sure that there was a high probability that it would not happen again.

How long would that stop be?

Let's look at some historical data...

How long would that take?

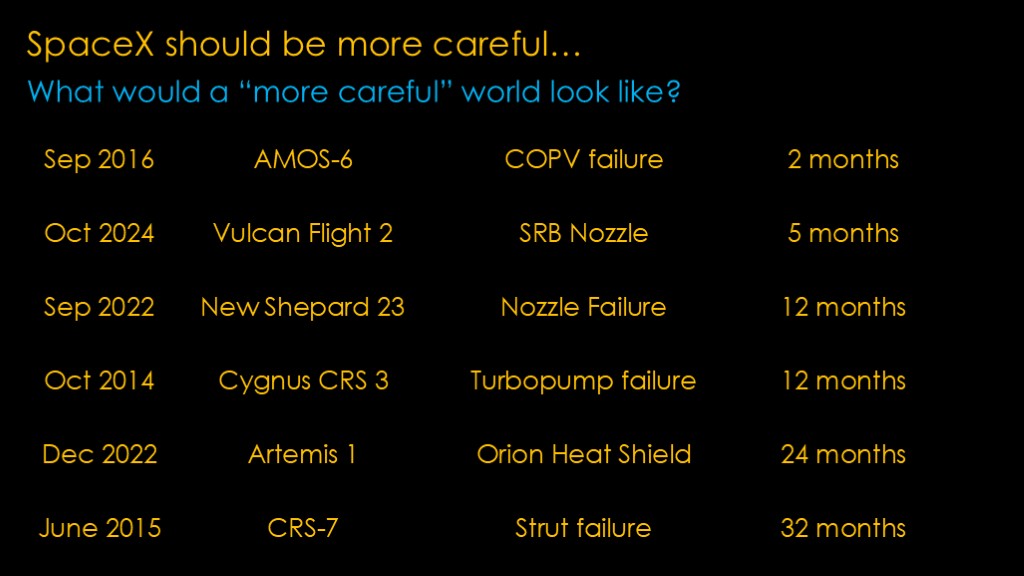

Let's look at some failures and how long the accident investigation took. This time does not include the time to next flight.

In September of 2016, a Falcon 9 exploded during a static fire test on the ground due to a pressure vessel failure. That investigation took 2 months.

In October of 2024, there was a SRB nozzle failure on the second flight of Vulcan. 5 months

In September of 2022, New Shepard had a nozzle failure. 12 months.

In October of 2014, Antares had a turbopump failure. 12 months.

On Artemis 1 in 2022, there were issues with the Orion capsule heat shield. 24 months

On June of 2015 during the CRS-7 mission, a strut failed in the second stage. 32 months.

Investigations take a *long* time if you are following usual procedures.

Let's just draw some delays on the graph of 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

I don't think you are going to hit "more careful" with a delay shorter than 6 months, and it could take up to 12 months.

Starship is currently flying roughly every 2 months, and with booster reuse showing up soon, let's assume they will continue at 2 month cadence.

That gives us 4 flights during a 6 month standdown, and an additional 3 flights if it stretches out to a year.

That gives us a question...

Is the program in better shape flying 4-7 more test flights, or doing investigational homework for 6-12 months?

(read)

This seems like it's an absolutely nuts way to run a launch company, but it's also pretty clearly the quickest way to get to solutions that work and are close to optimal.

The flight 7 and 8 failures are setbacks for the program, but an 8 week delay is barely within the schedule measurement error in most programs.

So I think it's going to be fine.

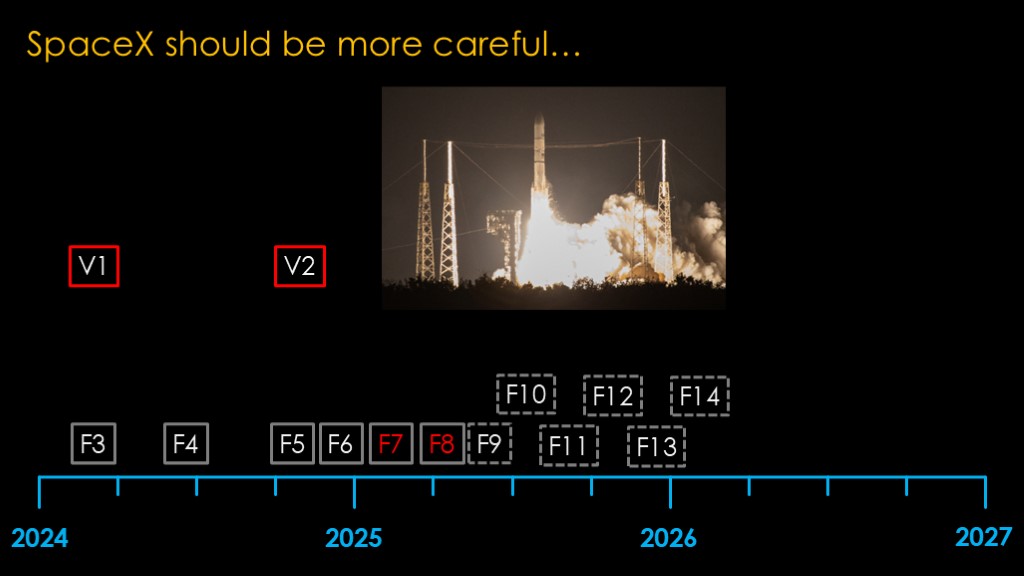

One final point on this timeline.

Rockets done using traditional design approaches start out slowly. ULA's Vulcan flew in January of 2024 and then again in October 2024. It is functional but not really operational - ULA has to go through the ramping up process before it is launching at a quick rate.

Starship is not yet functional but it is already operational - SpaceX already knows how to build and launch full Starship stacks every 6 to 8 weeks. That means we can expect that when it does become functional, it will be able to fly *a lot* right off the bat. SpaceX has front-loaded the ramp up process.

Remember the pattern we saw when SpaceX was developing first stage landing for Falcon 9. They very quickly went from not being able to land a first stage at all to doing it almost every time. At some point, Starship is going to reach that same point.

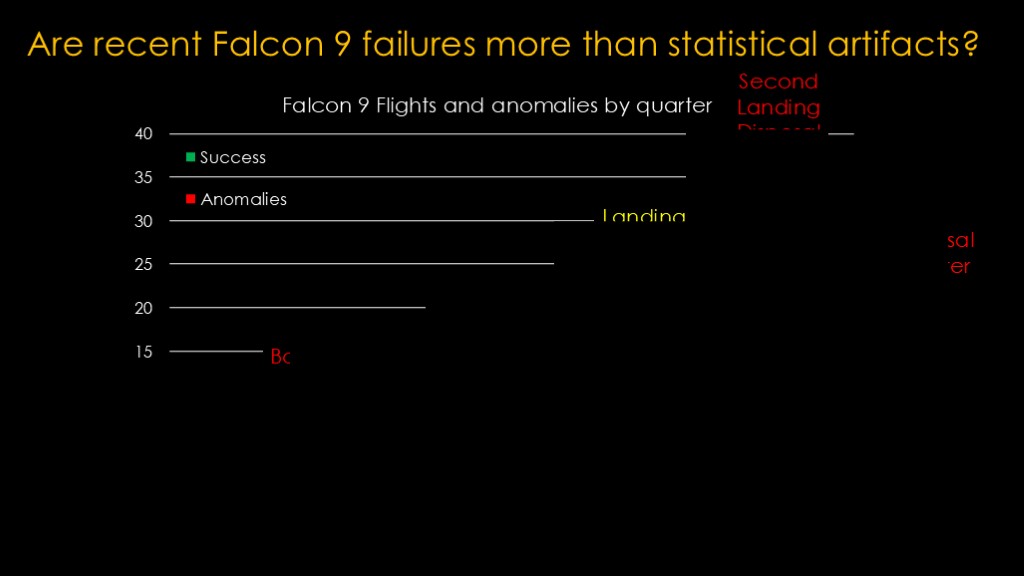

There's also been something different going on with Falcon 9 recently. I was recently asked whether the recent issues on Falcon 9 were normal or something new. I had an initial reaction but it's better if we look at the data

This chart shows the flight and anomaly rates by quarter. I've ignored Falcon Heavy because there aren't many flights.

We'll start in 2020. The first quarter had two landing failures; the first was due to incorrect wind data and the second was due to cleaning fluid trapped inside of a sensor. 2020 overall had 24 successes and 2 failures, for a 7% failure rate

2021 looks fairly similar. The first quarter had an engine shut down on ascent, and that led to a landing failure. Like 2020, the remaining 3 quarters were clean. 31 successes and one failure for the year. 3% failure rate.

2022 was the start of the big Starlink ramp up. 61 flights, no failures

2023 gives us 3 clean quarters, and the 4th quarter with a single landing failure. The landing was successful but high winds and waves meant the booster wasn't secured and it tipped over. 95 successes, one post-landing failure.

If we ignore that failure, Falcon 9 went 11 quarters and 179 flights without any anomalies.

That brings us to 2024. Two good quarters, then a fairly concerning third quarter. Flight 354 had a liquid oxygen leak that led to second stage engine failure, the booster on flight 367 caught on fire during touchdown and fell over, and in 378 the second stage deorbit burn ran for an extra 500 milliseconds and the second stage landed short of the targeted disposal zone.

Three failures versus 128 successes for a 2.3 % failure rate. Three failures in a quarter is a big deal after 13 clean quarters.

In 2025, we've seen another disposal failure on flight 431 where the second stage did not relight and the stage made an uncontrolled reentry over Poland 18 days later, and a booster fire that damaged a landing leg in flight 443. That's 2 failures and 24 successes, for a 7.7% failure rate for the quarter.

The cluster of the errors that we've seen is unlikely to be random chance. What is going on?

Is it booster age - are the older boosters more likely to fail? One of the boosters that caught on first was on its 23rd flight, so that could be due to the age of the booster, but the fire on the most recent landing was on the 5th flight, so it's unlikely to be age related.

Is SpaceX trying to hard to optimize their costs?

That's certainly a possibility. With the Falcon 9 reuse model, the big drivers for the cost of a flight are the cost to refurbish the booster before reflight and the cost to build new second stages, and cost reductions there could easily go too far and lead to reduced reliability.

Losing a booster on landing now and then isn't that big of a deal, but second stage problems are troubling as the Falcon 9 upper stage has been as close to perfect as one could ask for in the past.

My estimation is that they are pushing hard to keep reducing the price per launch as the launch cost is a big driver for starlink costs, especially with SpaceX targeting up to 175-180 Falcon 9 launches in 2025.

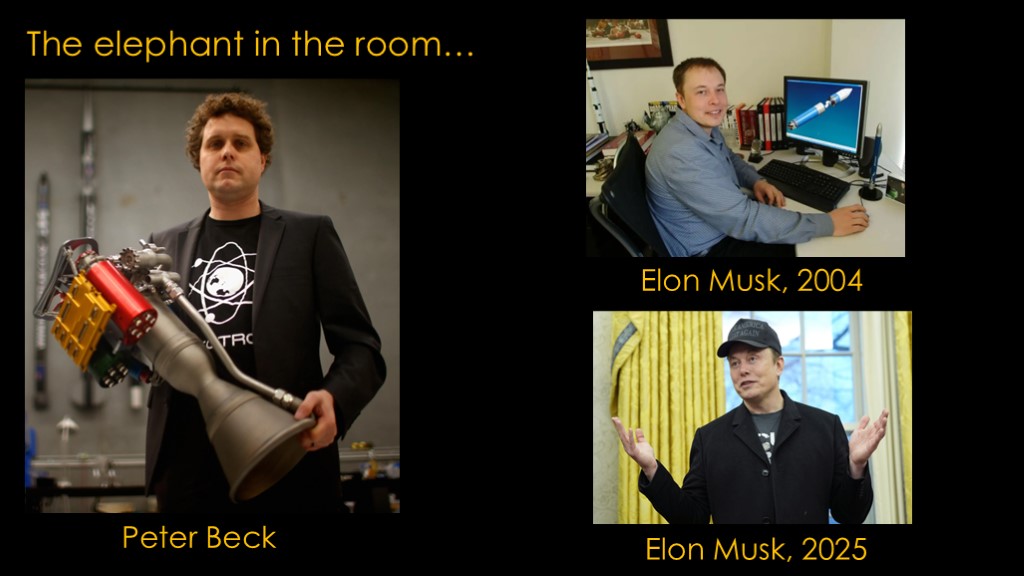

This discussion wouldn't be complete without a discussion of the elephant in the room...

It's been pretty obvious in my videos that I have a lot of respect for Peter Beck, and in fact I think he's exactly the kind of founder and CEO that a small rocket company needs. He is both obsessed with the technical side of rockets and other space hardware and very skilled at running the business side of Rocket Lab. The difference between the new space and old space way of doing things is largely the difference between founder-run companies and "executive run" companies.

Peter Beck and the early Elon Musk had a lot on common. Both obsessed with space, both wanting to run lean competitive companies to make launch cheaper. Musk had this distraction in that he was also running Tesla, but it seemed clear that SpaceX was his real baby.

That Elon Musk no longer exists. Things started changing when decided that he wanted to own and run twitter, and then his move into politics have cemented the change.

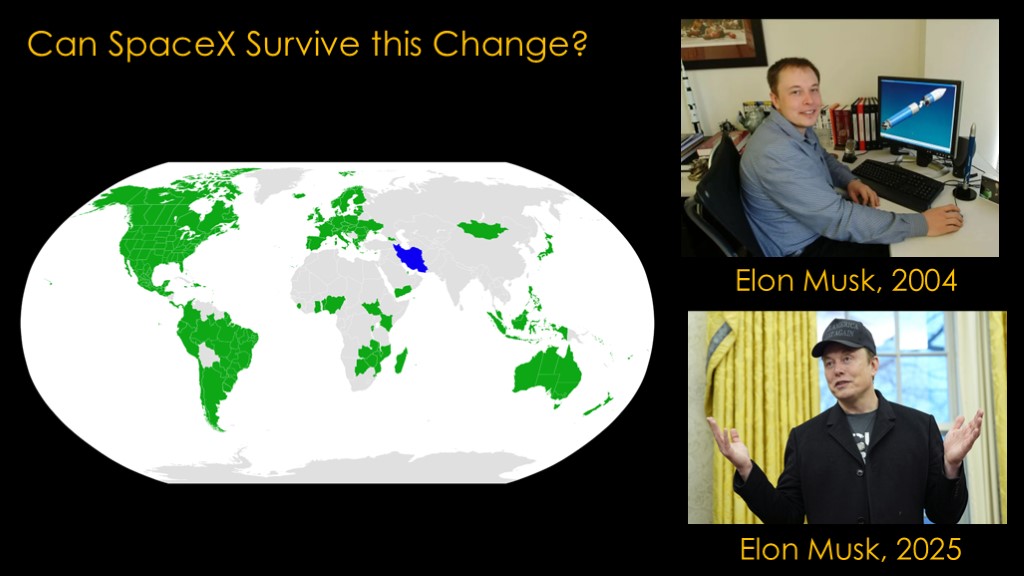

Can SpaceX survive this change?

Nobody knows the answer to that, but I do have a couple of thoughts...

The first is that there is no more critical person to the continued success than Gwynne Shotwell, who has been president and chief operating officer for SpaceX since 2008. She's reached an age and level of success where she can retire whenever she wants, and there's no obvious replacement for her at SpaceX.

My second thought is that SpaceX has a lot of contracts with both the department of defense and NASA, and those organizations have very specific ways of working with their contractors, ways that I do not believe align well with how Musk is currently operating. They especially like predictability.

My third thought is that Starlink is the big driver for SpaceX revenue right now, but providing service in other countries requires the approval of those countries. That could be more problematic in the future.

I have talked about the "Anybody except SpaceX" launch market in the past, and I suspect there will be a "anybody except Musk" space-based internet market.

Is SpaceX losing it?

I don't think we have a clear answer to that question right now, but I think the answer is probably "no".

It seems a big ridiculous to think that blowing up two flight versions of the biggest rocket ever to keep moving quickly is the right decision, but at this point it seems like the right decision, and there's certainly no sign that Starship development is slowing down.

I originally thought the Falcon 9 failures were an issue. I think they are a bit concerning but we'll need to keep watch and see if any more issues show up.

If you are having mixed feelings about SpaceX, maybe this might help.